Swetnam describes several guards, but only one stance for use with the rapier. He recommends placing the left foot pointing forward and to the left, and the right foot immediately ahead of it. The left leg is partially bent and the right leg is almost straight, with the thighs almost touching.

Figure 3. Foot position.

“…the heele of thy right foote should ioyne close to the middle ioynt of the great toe of thy left foote, according to this Picture, yet regard chiefly the words rather than the Picture.” (p. 85)

“… alwaies set your rapier foot right before the other, and so neare the one to the other as thou can…” (p. 86)

“Furthermore, in standing in thy guard, thou must keepe thy thighes close together, and the knee of thy fore legge bowing backward rather than foreward; for the more that thou holloweth thy bodie, the better, and with lesse danger shalt thou breake thine enemies thrust” (p. 88)

Figure 4. Swetnam’s True Guard, front and side views

While this stance is very narrow, it is not out of line with other early seventeenth-century rapier systems such as that of Salvator Fabris[1]. This stance is not particularly mobile, but Swetnam rarely recommends taking more than one step during a given fighting sequence. The majority of the fencer’s weight should be on the left leg, leaving the right leg ready for a quick forward lunge or a backwards void. It’s not mentioned in the text, but I recommend keeping the center of balance a few inches forward of the rear leg in preparation for lunging.

As to the upper body, Swetnam recommends an extremely square posture, facing directly towards the opponent and leaning slightly forward.

“and bowing your head something toward the right shoulder, and your body bowing forwards, and both thy shoulders, the one so near thine enemie as the other” (p. 85)

“…alwaies bearing thy full belly towards thy enemie, I meane the one shoulder so neere as he other, for if thou wreathe thy bodie in turning one side neare to thy enemie then the other, thou dost not stand in thy strength, nor so readie to performe an answer, as when thy whole bodie lieth towards thy enemie.” (p. 97)

In this style of rapier and dagger play, the dagger is nearly as active as the sword itself and is one of the keys to using the rapier successfully against other weapons such as staff. This squared posture brings the dagger farther forward and into the fight and makes dagger actions more powerful.

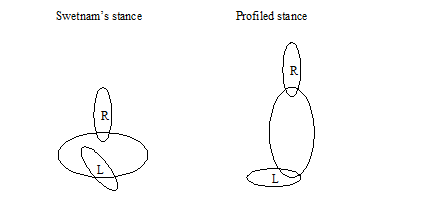

Those who recommend a profiled posture often argue that it presents a smaller target to the opponent. Swetnam’s posture offers a wider target, but one that is farther away from the opponent, as shown Figure 5.

Figure 5. Stance comparison.

“…for the more that thou holloweth thy bodie, the better, and with lesse danger shalt thou breake thine enemies thrust, before it cometh neare to endanger thy bodie…” (p. 89)

“Now the reasons which they shew to draw men into [a profiled guard], is first say they, the head bowing backe, then the face is furthest from danger or a thrust or blow: now to answere this aaine, I say, that although the face e something further from the enemie, yet the bottome of the bellie, and fore leg is in such danger, that it cannot be defended from one that is skilfull; and to bee hurt in the bellie is more dangerous then the face, whereasss if thou frame thy guard according unto my direction following the first Picture, then shalt thou finde that thy bellie is two foote (at the least) further from danger of a thrust” (p. 108)

While he initially recommends this stance for rapier and dagger, he doesn’t mention any change in the posture of the shoulders in his subsequent discussion of fighting with a single weapon. The plates for the single sword show the left shoulder drawn farther back than in the sword and dagger plates, but this is not discussed in the text and Swetnam (like most fencing authors) instructs us to chiefly regard his words rather than the plates. Swetnam’s single sword tactics include grappling and half-swording, both of which would be more easily performed from a square stance.

The primary guard position or “true guard” described by Swetnam is quite similar to some of the earlier “cut and thrust” guards. The right hand rests just outside and in front of the right thigh, with the rapier pointing up and forward. The dagger is held straight out from the left shoulder at cheek height, the tips of the two weapons nearly meeting directly in front of the eyes.

“Keepe thy rapier hand so low as the pocket of thy hose at the armes end, without bowing the elbow joint, and keepe the hilt of thy dagger right with thy left cheeke, and the point something stooping towards the right shoulder, and beare him out stiff at the armes end, without bowing thine elbow joint likewise, and the point of thy Rapier two inches within the point of thy dagger” (p. 85)

Figure 6. Swetnam’s true guard for rapier and dagger, as seen from above.

[1] Salvator Fabris, Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme, 1606.